Early in the 1970s, Bobby Ogolla chose a career which is religion to millions of people: Football.

In the middle of the 1980s, he was mature enough to know that at a high point, a player can be transformed into a people’s savior, the saint to whom they take their intercessory pleas. At a low, he is the devil incarnate, and the difference between these two ends is usually never more than 90 minutes.

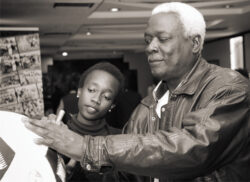

During the days they hailed him as The Six-Million-Dollar-Man, Ogolla sat me down and reflected ruefully:

“Life can be very difficult.” But the nation’s best stopper and most prominent problem player was poking as much fun as lament into it. “God must have created me on a Monday,” he told me when we talked about the great power packed into his 175-pound, 5ft 11½ inch sinewy physique. “He was fresh and rested after His Sunday break.”

As God helps only those who help themselves, Ogolla always ensured that body was well fed. When we settled into a restaurant and went over the menu, he asked the waiter: “Which among all these dishes has the most food?” Grilled steak, roast potatoes, vegetable salads and two glasses of juice followed.

This was the man who had been in the middle of some of Harambee Stars’ most difficult games since 1977. This was the man idolized as the Six-Million-Dollar-Man by his club fans one moment and vilified as the “chairman” of a certain group of dissident players who had no respect for club authority the next.

This was the man who took his fitness so seriously that he had set up his own private camp in the quiet of Nairobi City Park to work out on his own because he felt that team training was inadequate. He called his private space “Camp David.”

But he was also the man who reported for residential training only at the very last possible minute – after they had all but given up on him. In fact, sometimes he did not show up at all. In 1986, after taking part in Gor Mahia’s unsuccessful effort to retain their Cecafa East and Central African Club title, he disappeared from camp.

My job as captain was made very difficult by officials who insisted on taking part in the selection of players. As far as I was concerned, the team should have been selected by the coach. If he were to consult, then he could turn to the captain, the team manager and the doctor. Officials should stay in the benches just like other fans, because they have no idea of the technicalities involved

This earned him an indefinite suspension. But when the club’s fortunes plummeted and got themselves on firm course to abdicate their Premiership title, they contritely recalled him. But he told them he was unavailable. Neither the officials nor the fans knew what to do with him.

At that time, as he gradually worked the mountain of a plate on the table into a plain, eyes occasionally surveying the world outside, he told me: “My future with Gor Mahia is not bright. If there is no change in administration, my future with them is not very bright.”

His face was remarkably clear that afternoon, obviously the result of the long work-outs he had had at the Nyayo National Stadium as one of the 60 participants in a coaching seminar. This applied to his mind, too. The immediacy and clarity of his answers were striking. “I am weighing all the possibilities about my future. These possibilities include returning to Gor Mahia if I feel the setting is right”.

Ogolla traced his quarrel with Gor’s administration to 1982 when a players’ revolt led to the cancellation of the team’s return game against Madagascar’s Dynamo De Femia FC. The team forfeited that game and its place in the tournament. The Confederation of Africa Football, as usual, sent them a hefty bill. Heads rolled. Most notably, the team’s brilliant captain Sammy Owino, was stripped of the role. He soon after left for the United States where he has since become resident.

In came Ogolla. “My job as captain was made very difficult by officials who insisted on taking part in the selection of players. As far as I was concerned, the team should have been selected by the coach. If he were to consult, then he could turn to the captain, the team manager and the doctor.

Officials should stay in the benches just like other fans, because they have no idea of the technicalities involved.” Finding the going ahead hard, he quit. And because the administration over which he relinquished the captaincy in a huff was still in charge, life in the club had become one unending nightmare for him. “The problem is that simple, really – and that difficult,” he said.

Signing for another club practically out of the question. He spoke of his impossible position if he attempted to do that: “I am a prisoner. If I quit, the fans will hound me day and night. They won’t give my family any breathing space. And let me tell you this: it is even worse than that. My problems will begin at home. One of the fans who would not hear of my quitting is my own father who is more Gor damu than me. I love and respect him so you can see how difficult my situation is.”

He got quite emotional and almost aggressive as he argued: “Luhya and Swahili players have joined our club. What is wrong with Luo players leaving it? When I say this to fans, they tell me I am not talking like a Luo but the truth is I don’t consider our club a tribal one. It is open to everybody and I should be free to play or not play for it.”

Some cunning officials noted Ogolla’s close relationship with his father and made haste to the old man whenever they feared he was about to leave. That ended the problem. But the big man never stopped asking the big questions, and the main one – apart from team selection – was: How is the money being spent?

The answer to that usually came in the form of intolerable fiction. I asked him what he would do if God gave him the chance to live his life all over again and was surprised at the speed and emphasis of his answer: “I would never play football in Kenya. The officials are very bad. I play football only because I love it.”

But it was a love so strong that he couldn’t see a future without it. That is why he was participating in a coaching course. After his playing days were over, he planned to become a coach and that indeed is what he became. But it would take years before his club finally slayed the dragon of tribalism. It was his fate to live with it until the end of his playing career.

Impossible as he found his situation to be, another Harambee Stars player had actually said enough was enough and made a bold move out of his club. But he paid a steep price for it. On November 26, 1976, Edward Wamalwa had committed an act of what was clearly sacrilege. The mercurial defender, who had played for the national team for seven years, announced that he was resigning from the then mono-ethnic Abaluhya FC and joining Luo Union.

This meant that a Luhya player was joining a Luo team. It had never been heard of and possibly no Kenyan, player or fan, had ever contemplated such a profane act. Even the Daily Nation report of the following day did not miss the historic significance of Wamalwa’s decision.

It said: “Wamalwa, who has been a regular Abaluhya player since 1969, will make history if he joins Luo Union as no player of the Abaluhya tribe has played for a Luo club.”

Fans were incredulous and many wondered aloud if he didn’t need medical help. The great majority simply could not come to terms with this. But Wamalwa was serious. He made good his decision and indeed turned out for Luo Union. However, he had a torrid time with the fans. Every time he touched the ball while playing for Luo Union, a round of boos rang from the massed ranks of Abaluhya fans.

His place as the first Harambee Stars player to strike a blow against tribalism, though unsung, is well established. Wamalwa had fallen afoul of Jonathan Niva, one of the most influential personages ever to grace Kenyan football. Niva’s presence in Abaluhya, as AFC Leopards was known then, for better and for worse, was overwhelming. But Wamalwa had had enough of him. He swore that for as long as Niva called the shots at Abaluhya, he would never play for the club. But that was akin to wishing air away. Wamalwa played out his last years a pariah, shunned by “his people” and never quite accepted by the followers of his new club. But he did what Bobby Ogolla had second thoughts about.

Nevertheless, in Marshall Mulwa, Ogolla found a powerful and influential mentor. Although the player was a free spirit who regularly enjoyed his tipple when off duty as opposed to the puritanical coach, they were like-minded. Both loved the game passionately, were disciplined when it came to training, hated corruption and were against tribalism.

Mulwa’s appointment as Harambee Stars head coach elicited many snide remarks from Kenya’s “football communities”. They all boiled down to one condescending question:

“What do Kambas know about football?”

Harambee Stars’ first camp under Mulwa was at the Jacaranda Hotel in Nairobi. There, the players first learnt of the new order when being handed their room keys. Hitherto, sharing rooms was done strictly along tribal lines. But Mulwa distributed the keys with a list following this kind of pattern: Bobby Ogolla with Wilberforce Mulamba, Mahmoud Abbas with Dan Odhiambo, Ellie Adero with Jared Ingutia, J.J. Masiga with Otieno Bassanga and on and on. There produced a culture shock.

Mulwa had ensured that no two players of the same tribe shared a room. This had not happened before and it was going to be a steep learning curve for people who hitherto had difficulties even passing the ball to each other on the pitch, preferring to look for their tribal compatriots. “We were forced to learn to talk to each other,” goalkeeper Mahmoud Abbas said of that time.

Mulwa then gathered the players and gave them this edict: “When this camp breaks and you return to your clubs, I want you, Bobby, when you tackle Wilber and he falls to the ground, you must pick him up before resuming play. This applies to all of you. When the fans see you doing this, their attitudes will change as well. They must understand that you are not enemies, only competitors on the pitch.”

It was revolutionary and the effect was immediate. Mulwa proceeded to win three backto- back Challenge Cup titles – Dar es Salaam (1981), Kampala (1982) and Nairobi (1983) with Harambee Stars – with Bobby Ogolla playing a key role in defence.

Kenya’s Six-Million-Dollar-Man is now retired and plays little part in the proceedings of the country’s football. But no discussion of the game can be complete without reference to his contribution. Not only did he belong to a golden generation of players, he glittered noticeably even among those.